Is anyone else as annoyed as I with bumper stickers that say, "My child is an honor student at [fill in name of school]? What purpose does that bragging accomplish?

Easy answer: it reinforces the stereotype that it is an honor to be in a particular level of instruction. Abolish the term "honor" for these classes. Call them "Advanced, Grind, Nerd, Irregular, Developed, Extreme"--in other words, anything but "Honor."

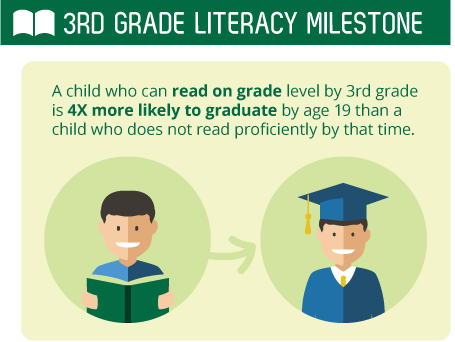

Don't get me wrong. I'm probably more enthusiastic about leveling students in sections than you ever were, but something has gone wrong in its public interpretation. Hence, the letter to Jody Stallings from a frustrated mother whose school moved her child into regular classes based on test scores. His weekly column points out the dangers of misplacing students. Yes, on a continuum of test results there will be students "on the cusp," but the student in question doesn't appear to be one of them. Take it from this former AP teacher: putting students into Advanced Placement classes who cannot read on grade level does no one an "honor."

"Q. My middle school child was an honors student last year. She worked so hard to get good grades. She did hours of homework every night and went to a tutor for help in math. This year I’ve learned that, due largely to test scores, she will be placed in regular classes. Now she says she doesn’t understand the point of working hard when you’re just going to get dropped to a lower level no matter what. I’ve asked the principal to move her back into honors, but he wouldn’t. How do I keep her motivated if she has to stay in regular?"

"A. Your question seems to begin with the assumption that last year she was properly placed in honors classes and this year she is misplaced in regular. But it sounds to me like it could be the other way around."

"In general, children who are appropriately placed in high-level courses don’t require tutoring to succeed. Honors courses are designed for students whose minds are ready for going above and beyond the standard grade level material. Mastering the curriculum should be challenging for them, but it shouldn’t require professional help.

"Secondly, no student should be spending hours on homework every night. That is a used car lot-sized red flag that the material is too difficult. The rule of thumb is ten minutes of homework per night for every grade level. A sixth grader should have about an hour. No student in K-12 should average two hours except perhaps high school seniors, and I can hear the parents of those seniors laughing at that suggestion right now.

"So it appears to me that the principal is trying to right a wrong. Many principals find themselves in the middle of a constant struggle between parents and teachers. Parents want their kids in honors at all costs, often because they think it’s an actual “honor.” Teachers want kids placed based on their developmental abilities and achievement. It waters down the class when too many lower level students are plied into upper level classes. Imagine a high-intensity aerobics class where half the participants are recovering pneumoniacs. (Do they still have aerobics classes? Just change that to “Jazzercise” then. Or “Extreme Yoga.”) It sounds like your principal is siding with teachers, and for that I award him a digital star: *.

"It’s not surprising that your daughter would use the perceived demotion as an excuse to give up. Taking the easy way out is endemic to adolescents. If a doorway to comfort is opened, you can be certain it will be used. Your task as the parent is to slam that door as hard as you can, lock it, and throw away the key. A great start would be discussing with her the difference between setbacks and failure. A setback is when one doesn’t get what one hoped; it often requires determination to get back on track. Failure is when someone gives up. Failure isn’t an outside explosion. It is an inner collapse. We can’t control setbacks, but we can control failure.

"Most of all, setbacks are a bruise. Failure is a tattoo. Once children start down the road of giving up, it leads to a habit of failure, and that habit can be so hard to break that it becomes part of their identity. So candid discussions with your child about doing her best are definitely required.

"Also required is recalibrating your expectations. If she got B’s in honors math, expect A’s in regular and hold her accountable. If she already was an A student and she finds that getting A’s in regular classes is too easy, then at the semester talk to the teacher (not the principal) about possibly giving honors another shot. If she stays in regular, then use the money you were spending on a tutor last year to enroll her in extracurricular courses this year (like an art class, a language class, or a new sport). With the time she isn’t spending doing homework, she can expand her horizons.

"So far in my career I’ve never seen anyone given a college scholarship in middle school (and Doogie Howser doesn’t count because he’s made up). Don’t worry that your daughter will somehow fall behind her classmates. True, they may take algebra a year before she does, but so what? While many of them will be learning the benefits (if there are any) of spending hours every night struggling with material that will be totally forgotten by next August, your daughter will be learning habits and character traits that will keep her soaring for a lifetime.

"Legendary coach John Wooden said, “Things turn out best for the people who make the best of the way things turn out.” Making the best of things is not a naturally occurring trait. This situation is a perfect opportunity for you to help your daughter learn it.

Jody Stallings has been an award-winning teacher in Charleston since 1992. He has served as Charleston County Teacher of the Year, Walmart Teacher of the Year, and CEA runner-up for National Educator of the Year. He currently teaches English at Moultrie Middle School and is director of the Charleston Teacher Alliance.

Personally, I'd like to call such classes "extreme." Then the bumper sticker could brag,

"My child is an extreme student at ____ elementary."